POLITICS OF THE FLESH

MARTTI LAHTI

Ilppo Pohjola’s Films and Images of the Body

When contemporary feature-length films made in Finland have dealt with political questions at all, their focus has mostly been on conflicts between social classes. Only a few Finnish filmmakers have examined the power politics related to sexuality and gender. The reasons for this may lie in the attitudes of financing institutions and the interests of filmmakers: the former have been reluctant to support, and the latter reluctant to create works that involve critical scrutiny of the power politics of sex and gender.

In recent years, Finnish feature films have been male-dominated. The most concrete evidence of this is the fact that for the last eight years, not a single film has been directed by a woman. Feature films have been dominated by scenarios constructed from a male point of view lacking in any awareness of gender questions. The most typical ones have presented nostalgic stories about Finnish males looking for liberation by means of travel. Whether directed by men or women, a heterosexual point of view has been dominant in these films.

In documentary films and video and media works, much more attention has been paid to the significance of sexuality and gender and their connections to various hierarchies of power, and this is a further indication of the influence of financing institutions on choice of subject matter. Film and video makers working with smaller budgets have had more freedom to produce a different kind of film.

Among male Finnish directors, Ilppo Pohjola has been the most consistent in seeking out new political ideas. It is my intention here to examine his films Daddy and the Muscle Academy (1991) and P(l)ain Truth) (1993). These two stand out from the majority of Finnish films both in terms of their subject matter and their provocative style. They do not aim for transparency of style or to camouflage their narrative solutions: both foreground their character as filmic constructions with a definite point of view.

The short feature P(l)ain Truth describes a sex-change operation. It is the story, presented solely in images and sounds, of a woman/man who surgically alters her/his female body to correspond to his/her masculine identity. Daddy and the Muscle Academy is a documentary on the life and works of Tom of Finland.

I am interested in the questions of power related to race, sexuality, and the body that both of these films raise. I am particularly interested in the ways in which they thematize the signs and traces that society’s exercise of power leaves on the body. Before proceeding to examine them, I want to make a brief survey of Pohjola’s other audio-visual works, with particular reference to their connection with these later ones.

AUDIO-VISUAL ESSAYS

In 1988, Ilppo Pohjola directed a made-for-television documentary titled Across Boundaries: Video as the Voice of Minorities. Its main focus is on the interaction between political art and marginalized cultures, and it is based on interviews with black film and video director Isaac Julien, video critic Michael O’Pray, video artist Graham Young, and video artist and critic Catherine Evans, combined with samples of political video art in Britain. These samples and the statements made by the interviewees emphasize questions related to race, sexuality, and gender, the same questions that have become essential to Pohjola’s own work.

Across Boundaries anticipates that later work, not only in terms of the political questions it raises, but also in its formal aspects. It can be seen as a kind of audio-visual essay, as filmic writing. That impression is reinforced by Pohjola’s (subsequently, almost ‘trade mark’) use of captions and short texts to punctuate and organize the piece. These do not function merely as written captions but also as independent images and graphic elements: thus, their content is not their only essential aspect, but their form plays an equally important role. In this sense, Across Boundaries is quite representative of Pohjola’s characteristic audio-visual style: ‘audiographic design’, which combines solutions from the realms of music video, art video, and film with those specific to graphic design. We might even say that his solutions favor ways of transcending the boundaries of these various modes of expression, e.g. those of the music video and graphic design. This is not surprising, since Pohjola has, in addition to his audio-visual productions, also worked in graphic design.

Ilppo Pohjola’s other early made-for-television works, Dialogue – 10 Chapters from the Visual Language of the Eighties (1989), Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1989), and The Edge of Art – One (1989) pursue questions raised in Across Boundaries and develop its esthetic solutions. Dialogue is a ‘post-cinéma vérité’ documentary on graphic artist Neville Brody’s visit to Finland. Ballad of Sexual Dependency translates photographer Nan Goldin’s slide show into the visual language of video and television. The Edge of Art is a collage video similar to Across Boundaries, and it deals with Finnish media art.

Stylistically, all three are related to one another and to Across Boundaries. Each one is built up as a montage of interviews and still or video images relevant to the subject. Dialogue differs from the two later pieces in that both camera and interviewer follow Neville Brody around the city of Helsinki, in a playful cinéma vérité manner, but without attempting to create an impression of truth or objectivity. Ballad of Sexual Dependency is based on the interplay between a studio interview with Nan Goldin, Nan Goldin’s photographs, and, surprisingly, shots and scenes borrowed from David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. In the manner of Across Boundaries, The Edge of Art emphasizes the artificiality of interview arrangements by means of sets, lights, and the use of video modalities: the interviewees are seen speaking in the studio, or only heard on the soundtrack, or are at times seen on video monitors placed in the studio. Of these works, especially the last two also move ‘across boundaries’: Ballad tests out the boundaries between photography and video, The Edge of Art those between media art and television documentary.

These early works do not take any noticeably strong or explicit stand on the comments and opinions expressed by the interviewees. Possible attitudes have been incorporated into the filming and editing--into what has been left out, what has been kept, and in the way passages from the interviews have been related to samples of the interviewees’ works. The result gives an impression of openness and trust in the audience’s ability to draw conclusions.

THE BODY AS BATTLEGROUND

The main works in Ilppo Pohjola’s career to date are the two most recent, the documentary Daddy and the Muscle Academy and the short feature P(l)ain Truth. They combine and develop the thematic and visual solutions from his previous work. Both films are characterized by a carefully planned and stylized audio-visual surface, one that, one might say, estheticizes their political themes by adding a stylistic component.

Both Daddy and Truth examine the interaction between the public and the private, and the effects that social fantasies have on our bodies. In the former, this becomes evident in the interaction between, among other things, Tom of Finland’s drawings and the bodies of homosexual males; in the latter, it is expressed as the conflict between a person’s body and that person’s gender identity. Both cases involve the desire and need to modify the body in order to fit it into the boundaries and models defined by personal identity. By emphasizing the traces left on the body by the desires, taboos, and fantasies of both society and the individual, Daddy and Truth question the body’s naturalness and stress its cultural determination.

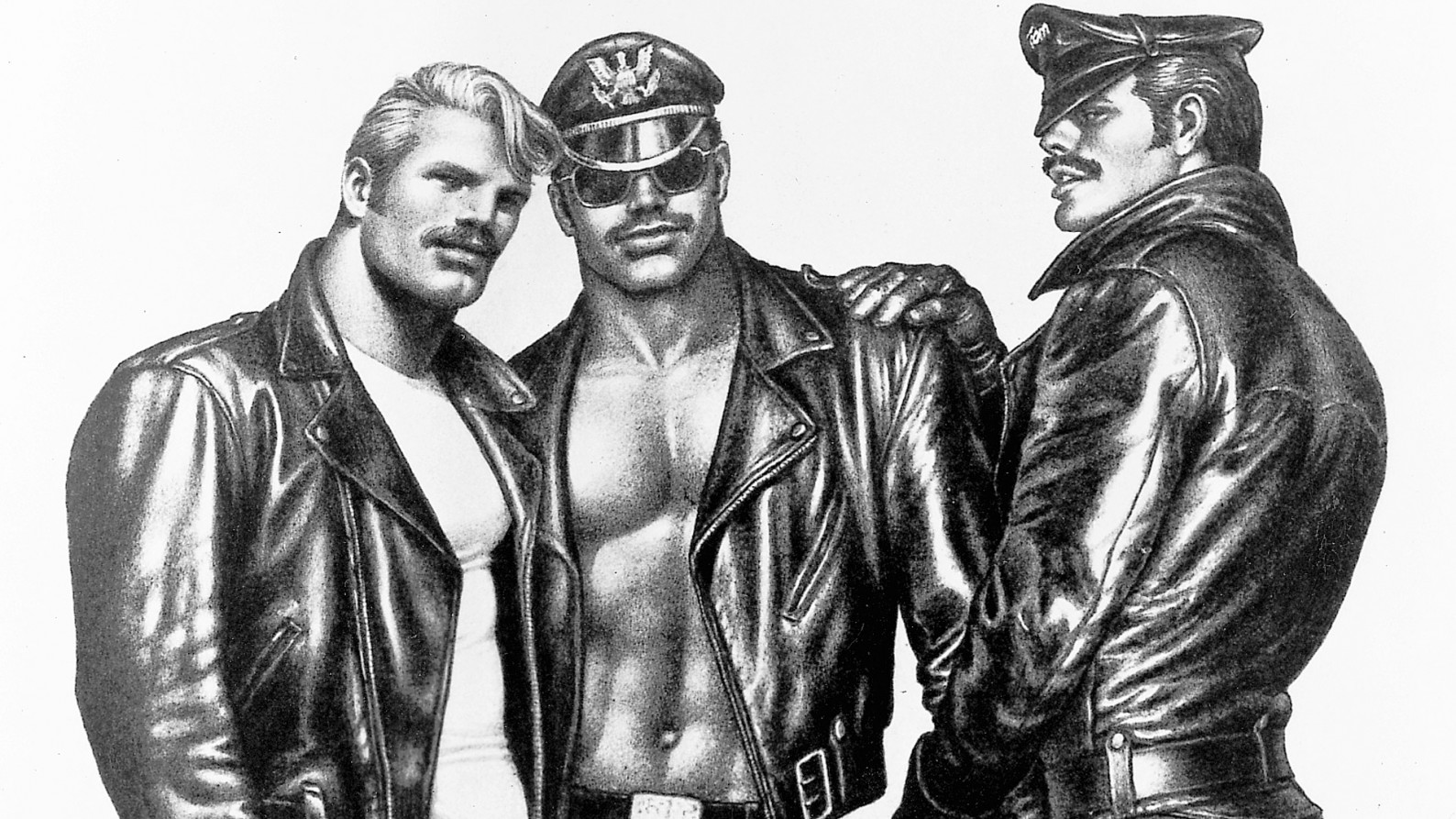

Daddy and the Muscle Academy documents Tom of Finland’s works and their importance to a homosexual subculture. Tom of Finland began his career in the late Forties/early Fifties by translating his own sex fantasies into visual representations in the privacy of his own studio. These images were published in American gay magazines and soon gained their creator international notoriety. Their impact on the homosexual community is not easily quantifiable, but they clearly affected an enormous number of people and caused them to modify their bodies and their fashions of dress and behavior to correspond to Tom’s images of leather-clad, muscular, and macho homosexuals wearing uniform caps. The iconography of these drawings has already become a part of Western visual culture. We have encountered it in Fassbinder’s Querelle and in Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, as well as in the physical appearance of Freddie Mercury and The Village People.

A consistent theme in Daddy is the interaction between Tom of Finland’s drawings and the bodies of homosexual men, its expression in the way the film’s gay men physically express their wishes, desires, and social fantasies. Both interviewees and images describe how the members of the gay uniform and leather subculture have identified themselves with Tom of Finland’s drawings as idealized images of the male body as hard and muscular. Structurally, the film expresses this in repeated juxtapositions of Tom’s fantasies with these men’s muscular bodies. This alternation extends the fantasies and their representations onto the surface of the body and generates a kind of dialogue between those representations and the live bodies.

By exploring the idealization of the muscular male physique and its sexualization, Tom of Finland’s men, the uniform and leather subculture, and this film all participate in further modifications of this ideal. One interviewee points this out when he emphasizes that Tom of Finland’s drawings “appropriated a certain macho type and sexualized it.” In other words, Tom’s images chose as their object, as the object of other men’s looks and desires, a male body which had been generally understood as the subject of heterosexual desire.

In Daddy and the Muscle Academy, the sexualization of the male body becomes one of the forms of resistance employed by gay culture. With their bodies, the film’s gay men combat the assumption made by heterosexual culture that gay men are effeminate, non-masculine. They use the traditional semiotics of (hetero) male culture, as expressed in a muscular body, to call into question such definitions of homosexuality. At the same time, they call attention to the signs that have been used to define heterosexual masculinity, and demonstrate their artificiality.

Large segments of our culture still believe that gay males are members a third sex, situated somewhere between the male and the female, and that they are, at the same time, ‘failures’ in terms of masculinity. It is the intention of Daddy’s steady flow of Tom of Finland’s drawings, and of images of the muscular bodies of gay males, to question the validity of such notions and to replace them with their own view of maleness. However, the film is not content to merely emphasize that view: it also plays with its semiotics and their exaggeration, presents us with the signs of gay culture. Rendering gayness and gay identity visible in this manner is an essential part of gay culture, because, as Cathy Schwichtenberg has noted, “sexualized visuality and identity are the most important premises for survival.”(1) As a culture repeatedly threatened with marginalization or invisibility by the dominant culture, gay culture finds itself constantly compelled to fight for its space in public consciousness.

One of the problems of such a strategy may well be that while it attempts to stabilize the visual semiotics of homosexuality by means of creating them, it may come into conflict with its other intention, the destabilization of heterosexual masculinity. (2) A strategy which sexualizes the muscular male body with its connotations of power ignores the fact that in culturally dominant representations, male sexuality has been traditionally equated with power; for men, power has been sexual. Thus it could be said that by sexualizing male power as well as the male body, Tom of Finland’s drawings may perpetuate cultural traditions which, by equating male sexuality and male power, have sexualized the oppression of women.

Tom of Finland’s pictures penetrate a binary opposition institutionalized by the dominant culture, one in which masculinity and the core of its dominance consist of muscles and a hard body. Discussing the ideal of the muscular male body, the British film scholar Richard Dyer has noted that “muscularity is a sign of power--natural, acquired, phallic.” Since they can be related back to physicality and biology, muscles are the last resort society can use as a justification for the ‘natural’ dominance of males. By their very existence, as it were, those muscles remind us that men’s superior physical strength ‘entitles’ them to social dominance. (3) This means that while the bodies of these men, and their images in Daddy, insist on a change in the dominant culture’s image of gay men, they simultaneously rely on processes and structures which maintain the hierarchy of power between women and men. Thus, we see a gay subculture and its visual aspects contributing to a normalization of a cultural ideal that bases male/female power hierarchy on differences in physical strength.

Daddy and the Muscle Academy does not explicitly take sides on the question of the gender-political dimension of Tom of Finland’s drawings. This is partly due to the fact that the emphasis of the film is on the significance of those images to the homosexual community. More explicit attention is paid to the racial politics of Tom of Finland’s images. One of the interviewees, film and video director Isaac Julien, notes that Tom had a tendency to represent African American males as oversexed and both frightening and desirable at the same time – in other words, in tune with the stereotypes investigated by a.o. Kobena Mercer and Homi Bhabbha. (4)

THE AILING BODY

Ilppo Pohjola’s last work to date, P(l)ain Truth, is a further investigation of interactions between the body and power. The question posed by the film is this: How close is the connection between our body and our identity? Does the body represent the plain and immutable truth about our identity? Or is the body (as Daddy implies) not subject to continuous modification by our identity and our society? Like Daddy, P(l)ain Truth proceeds to deal with the human need to create the body in the image of its identity.

The film relates how various social institutions (such as the educational system and medical science) compel human bodies and identities to conform with particular norms created by society’s exercise of power. On the other hand, in its final images, the film also describes the feeling of liberation that comes with the circumvention of social restrictions imposed on the body.

P(l)ain Truth questions the ability and power of medical science, and its medical outlook, to control people and their bodies. In its startling (audio)visuality, the film employs the layering of image, sound, and text familiar from Pohjola’s previous works. Image and body are dominated by the texts of the medical questionnaires that slide over them; their check-one-box questions are used to determine the respondent’s right to change the gender of his or her body by means of surgery. The questions, concretely inscribed on the body, are supposed to establish whether the ‘patient’s’ body and gender identity coincide. The film casts a critical eye on this ability of medical science to rule and maintain the boundary between the sexes by defining the connection between sexual identity (as seen by medical science) and the body. In this sense, Truth is an extremely concrete investigation of the ways in which power marks our bodies and modifies them.

The play on ‘pain’ and ‘plain’ in the film’s title points to this dialogue between power, the body, and identity. Pain, suffering, is a central factor in our Western culture defined by the Judeo-Christian tradition, clearly exemplified by the images of crucifixion which tell us a great deal about the glorification of pain typical of much of Western culture and esthetics. Not only in spite of Christianity but also because of it, our culture is able to take pleasure in punishment and to see beauty in suffering. The importance of suffering gains particular emphasis in regard to masculinity: it is made manifest in one of the dominant male images of Western culture, the suffering Christ. Indeed, masculinity must often be gained by means of various, and even painful trials. (5) This also applies to Truth, in which masculinity, or its outward manifestations, the body and its genitals, is achieved by the trial of painful, or at least arduous, sex change surgery.

P(l)ain Truth shows how the painful truth, the achievement of truth by means of physical change and pain, becomes the plain truth. Its final sequence differs from the rest of the film in its calmness, duration, and serenity. In it, we see naked men swimming; their bare ‘truth’, according to these images, would seem to consist of their bodies and genitals--but the main part of the film has already demonstrated to us the relativity and manipulability of that ‘truth’.

In that respect, as well, Truth aptly complements the question raised by Daddy, Ilppo Pohjola’s other film concerned with the body and its representations.

NOTES

(1) Cathy Schwichtenberg: “Introduction: Connections / Intersections.” The Madonna Connection, ed. Cathy Schwichtenberg. Westview Press, Boulder et al.,1993. p.7.

(2) See Cindy Patton, “Embodying Subaltern Memory: Kinesthesia & the Problematics of Gender & Race.” Ibid., p.88.

(3) Richard Dyer, “Don’t Look Now.” Zoot Suits and Second-Hand Dresses. An Anthology of Fashion and Music, ed. Angela McRobbie. First published in Screen, vol. 23, No. 3/4 (1983). Macmillan, Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire & London, 1989. p.205.

(4) See also e.g. Homi K. Bhabba, “The Other Question: Difference, Discrimination and the Discourse of Colonialism.” Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, eds. Russell Ferguson, Martha Gever, Trinh T. Minh-ha & Cornel West. The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, and The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 1990; Kobena Mercer, “Imaging the Black Man’s Sex.” Photography/Politics: Two, eds. Patricia Holland, Jo Spence, Simon Watney. Comedia, London, 1986. Mercer examines Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs in the light of White cultural fantasies about The Black Male.

(5) See e.g. Martti Lahti, “The Deficient and the Excessive. Masculinity and the Male Body.” Naistutkimus/Kvinnoforskning [Female Studies], 2 / 1992.

P(L)AIN TRUTH – A FILM FROM ♀ TO ♂

1993

15 min

35 mm/1:1,66/Dolby surround

4K DCP/1:1,85 Pillarbox 1:1,66/Audio 5.1

Starring LEEA KLEMOLA & RUDI

Written & directed by ILPPO POHJOLA

Cinematography ARTO KAIVANTO

Optical printing & rostrum cinematography SEPPO RINTASALO

Editing HEIKKI SALO

Set design ANTTI EKLUND

Sound mix KIKEONE

Music by GLENN BRANCA

Financial support AVEK, FINNISH FILM FOUNDATION

In co-operation with YLE/TV1

Producer ILPPO POHJOLA / CRYSTAL EYE

Film