How to Stage the Death of God

KAJA SILVERMAN

Although Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God in l882, it was not in his own voice, but rather that of a madman. He also rendered the event itself both temporally unlocatable, and unthinkable within the coordinates of an “action.” In the passage in which he does so, which represents one of the culminating moments of The Gay Science, Nietzsche describes a madman running into a marketplace before dawn, crying: “I seek God.” Since those who hear these words are atheists, they ridicule him. Then an odd reversal occurs. The madman acknowledges the vanity of his search; the God for whom he looks, he tells the others, is already dead. He also attributes the responsibility for this death to himself and his auditors. “God is dead,” he cries. “God remains dead. And we have killed him”. (p.181)

The madman’s listeners are astonished by his claim. God is not yet dead for them, even though they do not believe in him, and – in withholding this belief – would seem already to have relegated him to the grave. Their deed, as Nietzsche writes, is “more distant from them than the most distant stars”. (p. 182) The death of God will “require time to be seen and heard” by those who killed him, and that until this time comes, it will not in fact occur. Nietzsche’s speaker has consequently come not only too late to find God, but also too early to attend his funeral The “tremendous event” which he has announced is “still on its way, still wandering.”

Nietzsche does not tell us how long it will be before this event reaches us. He does, however, hint at the reason for its delay. Although there has “never been a greater deed” than the murder of God, its “greatness” is too much for us. (p.181) To stop believing in this figure would be to destroy the certitudes upon which civilization is based – to burn not only the “bridges” behind us, but also the “land” itself. (p. 180) It would be to embrace a meaning-making which is devoid both of origin and end – to give ourselves over to the limitlessness of signification. For finite beings like ourselves, however, the free play of the signifier feels like a prison-house of language, against whose walls we are constantly flinging ourselves. The only way to eliminate this sense of confinement would be to become gods ourselves (p. l81), and thereby to reinstate the Divine Maker.

Forty years later, Freud made evident that the news proclaimed by Nietzsche’s madman had still not reached those for whom it was intended. In the text in which he did so, The Future of an Illusion, he suggests that this is more for psychoanalytic than philosophical reasons. Civilization is based upon human renunciation. Religion represents a powerful agency for reconciling us to the suffering which this renunciation entails. It does so in much the same way that a dream does: through the imaginary fulfillment of what are fundamentally Oedipal wishes. But although functioning in a psychically specific way, religion addresses humanity at a collective, not an individual level. It generates what might be called “group fantasies.”

What generally passes in Western culture for “God” has its origins in the subject’s primordial desire for an omnipotent and absolutely loving father. (pp. 17-19) But whereas the father governs only the family, God rules the entire universe. He is consequently in a position to satisfy not just our infantile wishes, but also our larger existential lack, as well as to rectify the ever-increasing number of “wrongs” to which life subjects us. For reasons which are too profound for earthly understanding, but which we will ultimately understand, this reparation cannot take place now; rather, it will occur later, in another time. (p. 19) Assured of an eventual compensation for the renunciations which civilization demands of us, and persuaded that they are themselves part of the divine plan, we accommodate ourselves to them.

But Freud seeks in The Future of an Illusion to do more than trace the origins of the notion of “God,” and to identify the role which the latter performs at the level of the psyche. Like Nietzsche, he also attempts to expose this figure as a false pretender. Curiously, when Freud embarks upon this part of his project, he seems to forget a major aspect of his own argument: his claim, that is, that God has his origin in the father. He focuses only upon this figure’s illusory status. Freud also addresses his reader not at the level of unconscious desire, but rather at that of “reason,” the very mental faculty to which is most opposed to it. “The greater the number of men to whom the treasures of knowledge become accessible,” he writes in one passage from The Future of an Illusion, “the more widespread is the falling away from religious belief”. (p. 38) “In the long run nothing can withstand reason and experience, and the contradiction which religious offers to both is all too palpable,” he writes in a second. “Even purified religious ideas cannot escape this fate, so long as they try to preserve something of the consolation of religion”. (p. 54)

Fortunately, as is almost always the case when he violates his own most important principles, Freud’s unconscious begins symptomatizing wildly at the point that he embarks upon this mad project. As a result, The Future of an Illusion is riven through and through with contradictions. First of all, Freud defines “illusion” in ways which render null and void his own recourse to reason. He refuses to characterize it in the customary way, as a “fiction,” or “semblance.” A “reliable” illusion, he argues, is not one which is actualizable, but rather one which succeeds in fulfilling unconscious desire. Illusions can consequently only be judged only by the pleasure they provide; they set no “store” on “verification”. (p. 31)

At a certain point in his argument, Freud maintains that although most religions are illusions, some are delusions. (p. 31) At first it seems that he introduces this second category in order to provide the missing foil to “reason.” Here too, though, his terminology undermines his larger argument. Although a delusion, like an illusion, is first and foremost a vehicle for wish-fulfilment, it is amenable to the verification which an illusion escapes. It is only open to this possibility, however, because it defines itself over and against what is generally called “reality” – because it constitutes a protest against “what is”. (p. 31) Any attempt to disrupt a delusion by showing it to be at odds with actuality would therefore only reinforce it.

Eventually, it also becomes apparent to Freud himself that the opposition of “reason” and “illusion” is unsustainable. Even his own atheism may be based upon unconscious desire, rather than the unimpeachable logic he imputes to it (53). Freud now establishes a new line of defense: although his claim that there is no God may be an illusion, it is certainly not a delusion (53). But part-way through The Future of an Illusion, his argument takes a psychotic turn. He begins imputing to the reader things that she has not said. (pp. 21-56)

The words in question constitute a more and more heated refutation of the claims Freud makes on behalf of reason. Over time, they also occupy an ever-larger part of his text. It soon becomes evident that the author of The Future of an Illusion is not speaking to an external auditor at these moments, but rather to that within himself which contradicts what he is saying. He even imputes to this agency the same persecutory intent that President Schreber imputes to his doctor, Fleisig, in Freud’s famous case history of him. “What a lot of accusations all at once!” Freud protests at a key point in this “dialogue.” “Nevertheless I am ready with rebuttals for them all… But I hardly know where to begin my reply”. (p. 35) This would be a textbook instance of paranoia, were it not for the fact that what the father of psychoanalysis exteriorizes in his attempt to disprove religion is no ordinary internal “enemy,” but rather himself as psychoanalyst.

We come next to the title of the work under discussion. Were we to excerpt from The Future of an Illusion only those parts of it in which Freud himself explicitly speaks, we would expect the work to be called “The End of an Illusion,” or “The Beginning of Reason.” Instead, Freud projects into the future the very thing he claims to be ridding us of in the present. Near the end of this text, he acknowledges as much. In his attempt to resolve this contradiction, he also resorts to the same logic of postponement upon which religion depends. “The voice of the intellect is a soft one, but it does not rest till it has gained a hearing,” he says to his “opponent.” “Finally…it succeeds. This is one of the few points on which one may be optimistic about the future of mankind. And from it one can derive yet other hopes. The primacy of the intellect lies, it is true, in a distant, distant future, but probably not in an infinitely distant one”. (pp. 53-54) Freud also goes on to “unhedge” the “bets” which he makes in the last sentence of this passage by locating the moment in which reason will reign over mankind in an even more remote future that that imagined by Christianity: “We desire the same things, but you are more self-seeking than I…You would have the state of bliss begin directly after death”. (p. 54)

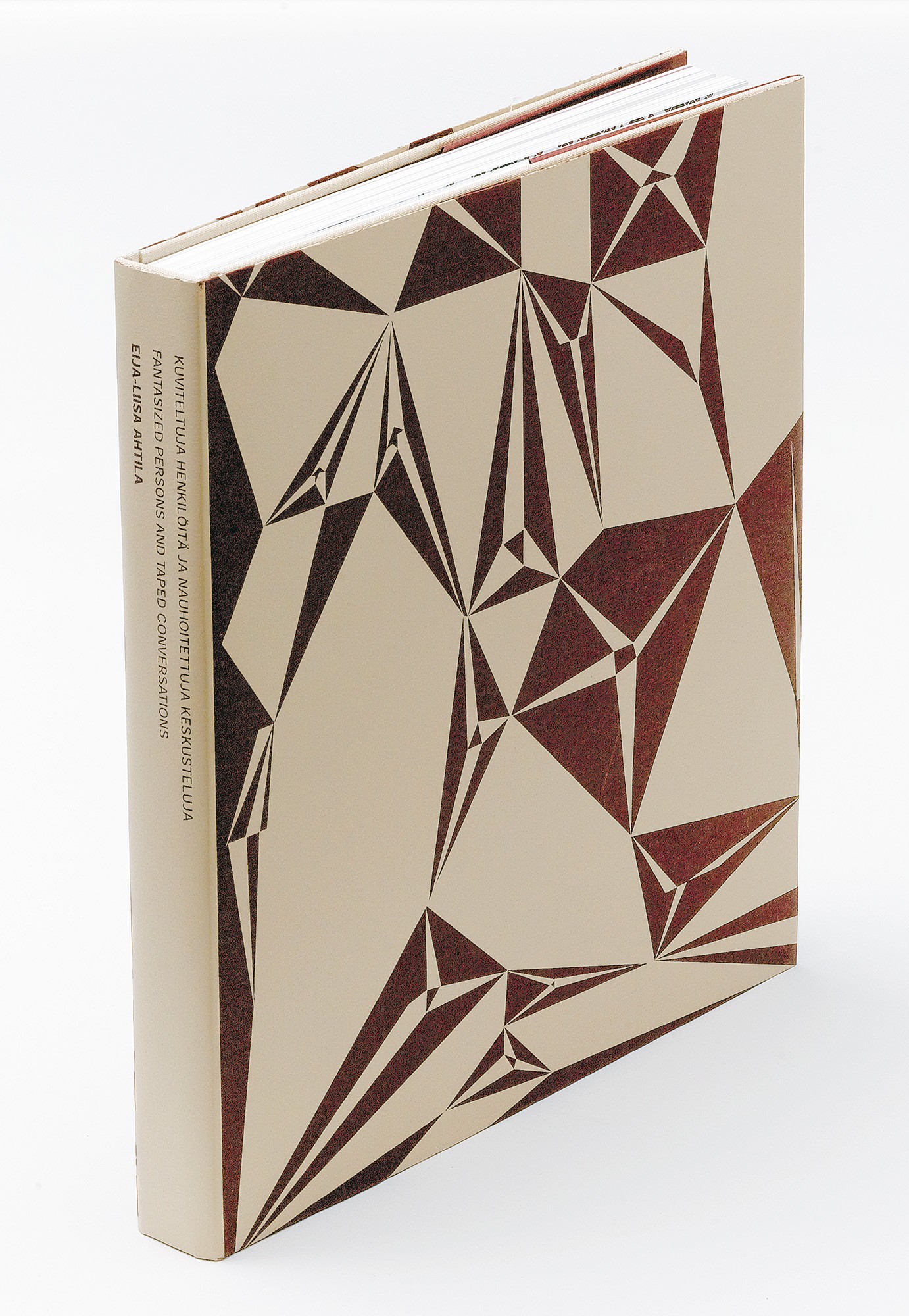

As must be evident by now, Freud no more succeeds in exorcising the divine ghost than Nietzsche does. In the pages that follow, I will attempt to show that this is because Freud leaves the mother out of his account of religious illusion. I will introduce this all-important figure into the discussion through a detailed analysis of another work which is centrally concerned with the death of God: Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s Anne, Aki and God. In her l998 installation, Ahtila transects this “tremendous event” at a later moment in its “wandering” than either Nietzsche or Freud. She then takes us beyond the twilight of the Gods to the total eclipse of the sun.

Anne, Aki and God is loosely based upon a taped interview with a recovering psychotic. If it were possible to abstract the story Ahtila recounts in it from the extraordinary form she gives it, we might summarize it in this way: God appears on a 3D screen to Aki, a man who works for Nokia Virtuals, and informs him that he has a girlfriend, Anne. Anne has blond hair, long legs, a well-proportioned body, and a plain face. She is as an aerobics instructor, and she wants to visit Aki. Aki tidies his apartment in anticipation of her appearance, in response to God’s suggestion that he do so. Anne comes directly from an aerobics class, and is out of breath when she arrives. She subsequently “fills” Aki’s life. Eventually the two become engaged, and Aki bids farewell to his single life with a ceremonial bow. At some point in time, Aki does two things which make Anne jealous. He opens the door of his apartment to Madonna, and he sleeps with hundreds of call-girls. Anne forgives Aki for these “infidelities,” though, since he tells Madonna that he is “already hooked,” and since his many one-night stands are part of his “education.” Aki recounts this story, which he at characterizes at several points as a “psychosis,” to two off-screen speakers. He does so after extended medical treatment, which stops the “voices” in his head, and so cure him.

In fact, though, nothing happens in this way in the way I have just described in Anne, Aki and God. Indeed, in a sense, nothing happens at all, since what we see and hear consistently exceeds the category of an “occurrence.” First of all, the installation consists not of one videotape, but rather of seven, all playing simultaneously: five devoted to Aki, one to God, and one to Anne. The God tape plays on a large screen, and the Aki tapes on video monitors, which are lined up in two columns in front of it – three on one side, and two on the other. Together, these six displays assume the form of a horseshoe. The Aki monitors rest on a wooden support structure which is lower on the left side than the right.

The Anne videotape plays on a screen which is positioned at a considerable distance from the others, and cannot be seen at the same time. This screen extends from the floor upward, and produces “life-size” representations of the character to whom it is devoted. A woman sits in a chair across the room, with a lamp at her side. She faces the screen, as an apparent spectator to what it shows. This is not the only “real” element in Anne, Aki and God. A bed has also been positioned in front of the God screen, horizontally.

Each of the tapes derives from an audition, and is marked as such through the mise-en-scène, the inclusion of off-screen voices, and/or what the actors say and do. In the God tape, Ahtila marshals two of the classic signifiers for a theatrical “tryout”: a script, and a chair positioned upon what seems to be an empty stage. The two different actors who sit in this chair also provide different interpretations of what is effectively the same text. The Aki tapes are also full of theatrical elements. The bedroom in which each tape begins is later shown to be a set. The off-screen voices to whom Aki responds could be seen as interviewers or doctors, but the primary function they serve is to provide the “prompts” to which this character responds. And in the Anne tape, six women apply for the part of its “protagonist.”

In all but the last of these tapes, the camera appears to be hand-held, and so to participate in the provisionality of what it shoots. And although the camera rests on a dolly in the Anne tape, there is something arbitrary about the positions it occupies, and when it moves. As a result, it too seems to be trying out a range of movements and positions, rather than “capturing,” “recording,” or any of the other activities we usually associate with a photographic apparatus.

The notion of an audition is central to Anne, Aki and God in a number of other ways as well. First, a different actor plays Aki on each monitor, and Ahtila prevents us from resolving the challenge which each poses to the existence of the others. All five Aki’s speak almost exactly the same words; do so in response to identical questions; and occupy the same space. However, each proceeds at his own speed, pauses at different points, and parses his word according to his own sense of time.

Far from attempting to mask this temporal heterogeneity, Ahtila makes it a central part of the viewer’s experience. Although she “resynchronizes” the five Aki screens at the beginning of each new section, she allows them to diverge in between. As a result, each of the Aki’s utters the same words at a different moment. The way in which Ahtila periodically realigns the Aki tapes only constitutes a further provocation to think outside the coordinates of action. She immobilizes each of the Aki’s in a surprising bodily position for an extended period of time, until the others “catch up” with him. Whenever this occurs, Aki seems to leave the domain where events occur, and to enter the one where feelings are felt. These “freeze frames” occur at divergent moments on each of the five monitors, last for irregular periods, and evoke extremely heterogeneous affects.

In addition, each Aki inhabits his role in a way which is specific to his own bodily coordinates, and imputes to the character he plays a different relationship to the words he speaks. Sometimes we seem to be looking at an actor playing a fictional character. At other times, we seem to be watching an actual actor playing a fictional actor, who is in turn playing a fictional character. On yet other occasions, we seem to be observing an actor play a fictional character who is himself somehow “split” or “doubled” – a character with such an acute awareness that he is being watched that he becomes a kind of spectator to his own performance.

Each of the five actors who represents Aki also promotes a different “diagnosis” of his “illness.” Depending upon the monitor at which we are looking, this figure suffered from psychosis in the past, but is now cured; still suffers from it, at least intermittently; was never psychotic, but rather retreated to the world of his imagination in search of the happiness which eluded him in actuality; was saner before his cure than after it, since it is actually the “real world” which is mad; or suffers from a delusion which is internal to normative male subjectivity, and so constitutes less an exception than the rule. The cacophony of different voices which we hear when positioned inside the main part of the installation nevertheless all make an equal claim to being what they are, which is not so much the “real Aki” as a “potential Aki”; they constitute something like “simultaneous possibilities.”

Although much of what I have just described eludes the category of an occurrence, it seems at first to fit squarely within the parameters of a live performance. In the theatre, as in Anne, Aki and God, events do not happens for once and for all, but rather over and over again. They also happen differently each time, not only when performed by a range of actors, but also by the same ones over successive nights. In the theatre, too, it is also difficult to determine when an audition begins and ends, and when it passes over into an actual performance. Finally, since no interpretation of a role can ever claim to be the one which fully and finally defines a theatrical character, the latter also exists in the mode of an infinite potentiality.

However, the sounds and images in Anne, Aki and God can no more be subsumed to a theatrical than to a quotidian notion of “action,” since they are prerecorded. Although they abolish the fourth wall, they also render it absolute. And while being volatile and ephemeral, they are also fixed, and perdure. So as to make certain that we understand this, Ahtila organizes her dizzyingly kaleidoscopic installation around an extended cinematic metaphor. Each of the five Aki’s begins the story which he recounts in this way: “One night when I was lying in my bed I felt as if I had been shot through the chest with a shotgun….That started the film in my head. I went into a psychotic state in which I saw images, I saw people who do not exist, I saw them in 3D. For instance I saw God on a screen on the wall.” Later, Aki also says that this film plays over and over again in his head, like a loop, which is precisely what each of the Aki tapes is itself.

Finally, we come to Aki’s strange agentlessness. He says at the beginning of the installation that his “psychosis” led neither to actions nor words, making it difficult to characterize him as actant even in the extended sense suggested by J.L. Austin. Aki also has frequent recourse to verbal formulations indicating that he was not the author of the film which played in his head, but rather the site at which it was made and shown. And although he does sometimes seem to be an actor within this film, it is in an unusually passive sense. He does not participate in the one-night stands; rather, “hot flesh” assails him from every direction. Even when carrying out an execution, it is not something he does, but rather something he is made to do.

The Anne tape makes it even more difficult to claim that anything “occurs” in Aki, Anne and God. It also further blurs the distinction between representation and reality. This tape consists of six successive interviews. Each applicant sits on a chair in front of a glass wall, through which we can glimpse the street outside, answering questions posed to her by an off-screen speaker. Ahtila masks both sides of the image for the duration of the tape, creating the impression that we are looking at it through opened theatre curtains. She also carries over the theatrical metaphor into the interviews themselves. The six women who appear in the Anne tape are all trying out for a part, and several stress their previous experience as performers. The space in which they sit is partially screened off from the street outside by open venetian blinds. Finally, it is for the role of a non-existent character, Anne that they are auditioning.

However, the women do not spend much time thinking about what Anne represents to Aki; instead, they project their own desires and fears onto her. It is also more about themselves than Anne that they are asked to speak. They consequently seem to be auditioning for the part via their subjectivity, rather than their acting skills. At least once in each interview, the interviewee also veers over into identification with Anne, at which point she begins to impute reality to her. On these occasions, it is not the actual woman who assumes Anne’s qualities, but rather Anne who assumes hers. Finally, Ahtila places one of the five women who auditions for the part of Anne in the chair in front of the Anne screen, inviting us to interpret the tape in its entirety as her projection. At the same time, though, she leaves open the possibility that this woman herself has been projected into the chair in which she sits by her video counterpart, through the sheer force of the latter’s desire.

The Aki tapes pose the same challenge to the traditional demarcation of “fact” from “fiction.” At the beginning of each of these tapes, Ahtila shows us the bedroom in which Aki is supposed to have seen the God screen. Later, we will understand this bedroom to be a stage set-up. But already at this moment in the installation something prevents us from fully suspending our disbelief. The wall behind the bed has been painted a bright video blue – the same blue which Ahtila will repeatedly associate with the God screen.

For a moment, this expanse of color has a profound Verfremdunseffekt. But then we realize that the blue wall locates within our perceptual field what Aki describes having seen in our psychosis. We even see the God screen in exactly the form he did. The physical presence of the bed further challenges our claim to stand outside the space of delusion. Suddenly, we are in the thrall of a disquieting thought. When we enter the main part of the installation we ourselves are, or rather could be, Aki

The notion of an “audition” derives its primary meaning and importance from the God tape. This tape begins with a long stretch of uninterrupted blue, during which there seems to be nothing to look at. After a while, the word “God” appears in white letters against the blue, as an apparent prelude to a divine appearance. Then the white letters vanish, leaving us staring again at a blank screen. Now, however, the field of video blue ceases to signify “the absence of representation,” and becomes indicative instead of God’s absence.

Just as we are we are getting used to the idea of being characters in a Beckett play, whose role is to wait for a non-existent deity, a pregnant woman appears. She sits in a chair on what seems to be an empty stage. The woman’s feet are bare, and she wears a black maternity dress, further reinforcing her maternal identity. She says, “I am here. I don’t care if nobody comes to see me. I won’t be offended if nobody sees me. I am not God because there is no God, I play God….I don’t look like your mother, but I am your mother. I will show myself to you in 3D like flesh. You wonder whether I exist. I look back at you. The eye with which you behold God is the eye with which God beholds you.”

By promising to show herself “in 3D, like flesh,” the speaker identifies herself as the Divine Being who appears to Aki at the beginning of his delusion. But she also clearly addresses us as well – and at the level of our unconscious desire. When she says that, “the eye with which you behold God is the eye with which God beholds you,” she indicates her general agreement with Freud’s account of religious illusion. God represents the exteriorization of an infantile fantasy – the fantasy of an omnipotent and all-loving parent. She also suggests that this fantasy is at the heart of our subjectivity, as well as Aki’s.

Both with her body and with the words “I may not look like your mother, but I am your mother,” though, she calls into question one of the primary claims Freud makes in The Future of an Illusion – the claim that this fantasy originates with the father. The pregnant woman reminds us that the child usually addresses its earliest demands to the maternal parent. It must consequently be around the figure of the mother rather than the father that the dream of an infinitely loving and powerful parent first coalesces.

But Ahtila’s project is not to reconstitute God in the image of the mother. It is rather to dispose of religious belief altogether. She therefore has the speaker differentiate herself from God even before drawing attention to her maternal status. With the words “I am not God because there is no God. I play God,” Ahtila also locates the origin of God not in the mother herself, but rather in the gap separating her from the parental “ideal.” Since this is both one of the most subtle and one of the most important aspects of Anne, Aki and God, I will attempt to frame it psychoanalytically.

The demands, which the child addresses first to the mother and later to the father, cannot be satisfied. Not only are they exorbitant in and of themselves, but they mask a more fundamental demand. What the child really wants is to be rendered “whole” or “complete.” But even if the mother were in a position to provide what is asked of her, it would be imperative that she refrain from doing so, since without lack there can be no subjectivity. As Winnicott was the first to understand, the mother should be “good-enough,” not “good-for-everything”; she should expose her limits to the child.

Unfortunately, the mother fulfils this crucial mandate only at great cost to herself. The infant subject typically responds to the partial satisfaction of its demands with extreme rage. This rage is predicated upon the belief that the mother is withholding what she has to give. It is at this point that our culture should step in with enabling representations of maternal finitude. Far from helping to extinguish the flames of the child’s anger, however, normative ideology still stokes it. It does so by keeping alive in all of us the tacit belief that everything that the mother could satisfy our desires if she wanted to.

As a result of even more strenuous ideological prompting, a diametrically-opposed perception of the mother begins to take shape in the infant psyche. The mother is not good-for-everything; she is, rather, good-for-nothing. In his late writings, Freud represents the exposure of maternal lack as the basis for the negative judgments the boy subsequently makes about her. The girl’s hostility toward the mother, on the other hand, is primarily fuelled by her belief that the latter has deprived her of a penis. In my view, both the boy and girl subject the mother to a brutal derogation because they continue to believe in her capacity to fill their larger existential lack. Deidealization constitutes an agency of revenge.

Not only does maternal disillusionment always have its roots in the illusion that she is capable of satisfying our demands, it also provides the support for a new set of illusions: those constitutive initially of the paternal function, and later of God. When the child fails to secure what it wants from the mother, it does not usually accommodate her limits, or acknowledge the impossibility of its own demands. Instead, it searches for another source of satisfaction. Because the father is so ready-at-hand, both physically and ideologically, it is usually to him that the infant subject now turns. As we will see, the paternal illusion fares better than the maternal illusion, since it is buttressed by the same principle which supports religious belief: postponement.

But when the pregnant woman tells us that she is not God, she does more even than mark the distance which separates her from the role the child calls upon her to play. She also invites us into a domain which most of us have never occupied: one located in the interval between maternal illusion and maternal disillusionment. The name of this domain is “finitude.” If we were to rely upon Freud’s and Nietzsche’s accounts of the latter, we would be at a loss to understand why anyone would accept the mother’s invitation. For Freud, to confront one’s finitude means to diminish one’s expectations radically—to accustom oneself to living within a narrow compass. For Nietzsche, it opens the door to a limitless freedom. Unfortunately, though, we are incapable of enduring this freedom. (pp.180-81)

Ahtila provides a very different account of finitude in Anne, Aki and God. We assume it not through grim resignation, or through heroically burning the “land” behind us, but rather by “playing” with the mother. To play with the mother is to stop imputing to her a fixed meaning. It is see her as what she really is: the first signifier in the ever-longer chain of unique signifiers through which each of us symbolizes our manque-à-être. But it is not merely that the mother does not have a fixed meaning, she does not have any meaning. Unlike all of the subsequent signifiers of our desire, which find at least a temporary signified in what precedes them, this first signifier has no prior term to which it can refer. It symbolizes “no-thing.”

As Ahtila helps us to understand, the shape which the mother initially assumes is completely arbitrary; nothing “grounds” her, or guarantees her authenticity; The one who occupies this position is also auditioning for a non-existent role. She is finite being whom we have called upon to represent what cannot be represented – something ineffable, impossible, irrecoverable. She does so in the only imaginable way: partially and provisionally. To understand this is to know that our lack will never be filled. But it is also to open up the category of “mother” to other actors and other interpretations, and so to set sail joyously on the sea of signification.

When the pregnant woman finishes speaking, the video monitor resumes its blankness. She returns four times, always “out of the blue,” and always in a different rhetorical mode. She seems to be intent upon showing us a few of the guises which the mother can assume. The first time the maternal figure comes back, she addresses Aki directly, and he “responds” from all five monitors. She talks with him about Anne. Ahtila clearly bases this conversation on the moment in Genesis when God tells Adam about Eve (2,.18-24) : But she changes a key element in the Biblical story. Whereas God gives Eve to Adam, thereby inaugurating the “trafficking in women” which Lévi-Strauss equates with culture, Ahtila’s speaker contents herself with reminding Aki of Anna’s existence.

The maternal figure invokes the story of Adam and Eve a second time in a later sequence. This time she introduces some even more important changes into it. She transfers the power to create from God to man. She also makes her late twentieth-century Eve an aerobics instructor. “In his silent lonely flat Aki created a woman for himself,” she tells us. “One night Anne stood at the doorway. She was out of breath. She had just been teaching aerobics.”

Since we are not accustomed to imputing a transformative power to heterosexual male fantasy, it is easy to miss the radicality of this shift. Making Anne a figment of Aki’s imagination rather than God’s still leaves her absolutely compliant to male desire. And then there is the fact that she is “out of breath” when she arrives at his door; that she is a “perfect woman”; and that she is an utter cliché. Aki does not create ex nihilo. His fantasy is clearly inspired by Madonna videos and Jane Fonda work-out tapes. It will be through this seemingly banal figure, however, that Aki accedes to the mother’s finitude.

No sooner has the pregnant woman “reminded” Aki about his girlfriend than she begins to “become” her. The next time she speaks, she imputes to Anne a dream of her own. In so doing, she carves out a space for the aerobic instructor’s psyche. She also suggests that Anne awakens from her own dream into Aki’s fantasy. Finally, she intimates that the former somehow anticipates the latter, and she recounts it from a position inside it. Not only is her language closer to an unconscious than a preconscious form of symbolization, but its tropes also derive from the subjectivity they evoke. And at the most important moment in this dream – the moment when the maternal woman utters the words “I am waiting for you” – she ceases to maintain any distinction between herself and Anne. “During the night [Anne] was dreaming,” she says. “Maybe she was partly awake and sensed what was happening…a sigh clung to the sides of the building. The sound got up to the terrace and went down the stairs. These sounds were mixed with a recurring whisper: ‘I am here waiting for you.’ She listened for a long time. Then the almost inaudible words filled her and she woke up.”

When the pregnant woman appears for the third time, she utters the words with which Freud should have begun the second part of his argument – words attesting to the unconscious nature of religious belief, and its imperviousness to reason: “No one believes in God because of irrefutable proof. That wouldn’t make people change their whole life.” She then identifies fantasy as the agency through which we not only enter religious illusion, but also exit it. She does so by again speaking from a position which is closer to the unconscious than the preconscious, and stylistically dependent upon another character’s point of view. This time the character is Aki, rather than Anna.

The language which issues from the overlap of her subjectivity with his is again intensely metaphoric, but it is more striking yet for its yoking together of contraries. “Aki is driving down the road,” the maternal figure says. “In the ditch there is cold snow. Otherwise it’s like summer…Here we have winter and summer simultaneously, like two blades of a knife side by side.” The form which these contradictory assumptions takes is also in excess of “conventional” unconscious symbolization. Freud writes that the unconscious has no capacity to say “no,” and can consequently say two incompatible things at the same time. It typically does so, however, by combining them, i.e. by dissolving the antithesis. Here, there is no such unification; the binaries remain sharply etched. There is also something lethal about them.

As the pregnant woman speaks, Aki engages in a parallel discourse. He describes the darkest moment in his delusion, invoking in the process two of the same tropes she does: the dead of winter, and a place where two disparate things abut. Once again, there is also a palpable sense of danger. But the violence which remains implicit within the maternal figure’s discourse now assumes an explicit form. “What shook me up most,” he observes, “was the incident when I had to execute someone in my mind. I know that I haven’t really executed anyone. It was filmed in my head. It happened on an icy lake in the frozen wintertime on the border on Finland and Russia. A good-for-nothing human being was being executed.”

As is no doubt evident by now, I took the phrase “good-for-nothing” from this sequence of Anne, Aki and God. I did so because the latter contains in miniature the entire account of maternal deidealization which I elaborated earlier in this essay. The mother is the “human being” whom Aki executes on the border of Finland and Russia. He does so by placing the knife-blade of disillusionment next to the knife-blade of illusion – by punishing a mother whom he still assumes to be omnipotent for her failure to satisfy him Aki says that he was “made” to commit this crime because it is “larger” than any of us – because the position of executioner is one into which we are ideologically interpellated. And it plays round and round in Aki’s mind because it seldom happens only once. Most subjects continue placing the knife-blades of idealization and deidealization together long after infancy.

Fortunately, Ahtila does not leave us stranded on the border between Finland and Russia. As soon as Aki completes his account of the execution, he remembers that Anne was there with him, and cared for him afterward. “She put on my coat for me,” he remarks tenderly. “It made me feel warm when she put my coat on. Same as when a girl puts on your coat and takes your hair out of the way.” This abrupt shift of conversational gears is shocking, as is the affective modulation which accompanies it; it seems indicative of a profound disassociation. Once again, though, Ahtila challenges our usual ways of thinking about emotional issues.

At precisely the same moment that Aki recalls Anne’s gesture, the pregnant woman’s tone also changes dramatically, and in apparent response to his. She stops talking about the psychic domain where winter and summer coexist, and addresses him and us directly. She also speaks with a new intimacy and candor. Whereas she initially put a brave face on her solitude, and later acknowledged her loneliness only obliquely, now she openly expresses her desire for our company. She also indicates that she at last has it. “I miss you,” she says. “I want to tell you something. And I will. I expose myself. I show you my face. I give you my life and my time.”

It might seem surprising that the maternal woman would claim to be “exposing” herself to Aki and us at the precise moment that Aki is talking about Anne, but Ahtila is using this word in a very special way. It signifies not the unveiling or uncovering of something hidden, but rather a revelation via reinscription. The maternal figure exposes herself to us through Anne. She is able to do so because when Aki stops talking about the “good-for-nothing human being,” and begins to take pleasure in his girlfriend’s little gesture of comfort, he permits a new maternal audition to begin. And in allowing the banal figure of an aerobics instructor to “try out” for the part of mother, he finally gains access to that aspect of the latter which he has previously denied: her finitude.

The audition begins in earnest in the next sequence, when Anne arrives at Aki’s door. The pregnant woman indicates as much by singing a stanza from an Olivia Newton-John song. “Stop right now. Thank you very much. I need someone with a human touch. Stop right now. Thank you very much. I need someone with human touch.” Since this song was often played in aerobics classes in the l980’s, Ahtila seems at first to be using it to make fun of Anne. But it soon becomes apparent that it is as Aki’s representative rather than Anna’s that the maternal figure sings it, and that there is as much profundity as humor in its lyrics. With the words of Newton-John’s pop song, Aki finally brings to a halt the endless screening of the execution film.

The last time the maternal figure returns, she provides what might be called the “official narrative” of Aki’s “cure.” She also does so from a new position: that of an omniscient narrator. “An ambulance drove Aki to the isolation ward in the hospital,” she recounts. “There he was in solitary confinement…. Later he was still psychotic. Thinking of Anne gave him immense pleasure… After heavy medication, he no longer heard any voices.” Even in this “case history” form, Aki’s story is manifestly one of loneliness and loss. The medical establishment has deprived him of his fantasmatic companion, and so of his pleasure. It has also closed down the space where the mother could be human. The pregnant woman speaks from a god-like vantage-point because it is the only one left to her.

The notion of a “recovery” does not figure at all in Aki’s final words; he speaks only of what he has lost. The latter category includes not only Anne, and – through her – the human mother, but also the person his fantasy might have allowed him to become. He utters his last, desolate words from within an aesthetic as well as an existential solitary confinement; mid-way through his monologue, the pregnant woman permanently vanishes, returning the God screen to its original blankness.

But Ahtila does not end Anne, Aki and God with the sequence I have just described. After Aki’s story reaches its apparent conclusion, it starts all over again. This time, a male actor occupies the position previously occupied by the pregnant woman. Ahtila emphasizes the importance of this change by having him say “I may not look like your father, but I am your father,” instead of “I may not look like your mother, but I am your mother.” And although the text which follows is otherwise identical to the one we have already heard, she makes it resonate in all kinds of new ways.

At first, we register primarily the normative aspects of the paternal figure’s masculinity. On the occasions when he speaks about Anne, he does not blur the distinction between himself and her, as the maternal figure does. He aligns himself with Aki, instead. When he describes Anne’s physical charms to the latter, he makes an appreciative gesture with his hand, transforming their conversation into an erotic exchange. And whenever he and the five Aki’s talk about Anne simultaneously, we feel as if we have just entered a locker room.

But the notion of an audition is much more strongly marked in the second part of Anne, Aki and God than it is in the first, and in ways that enormously complicate our understanding of paternity. Whereas the female speaker is already seated when she first appears, and articulates the words she speaks as if they “belong” to her, the male speaker initially stands with his back turned, smoking. He then puts out his cigarette, and moves toward the chair, like an actor about to try out for a part. Unlike the maternal figure, he also holds a script in his hands, from which he will later read. Finally, his delivery is much more classically “theatrical” than hers, further marking the distance between himself and the character he is enacting. With each gesture and verbal nuance, he proclaims: “I am not God, because God does not exist. I play God.”

It soon becomes evident that the male speaker is playing not only God, but also the father who plays God. Although he does not face us until he sits down, indicating that it is then that the audition officially begins, he begins “acting” much sooner. The exaggerated way in which he extinguishes his cigarette, the preparatory clearing of his throat, and even his turned back are all theatrical clichés. And he is no more “in character” in the paternal role than he is in the divine role. His hair is uncombed, he has a three-day beard, and his sneakers are dirty. He wears scruffy clothing, is clearly over-weight, and does not always know how to deliver his lines. He seems to be coming apart at the seams.

Immediately before telling us that “God is dead,” Nietzsche’s madman introduces an important metaphor: the metaphor of decomposition. With it, he raises the possibility that God is a compound entity, and that it is because we have not yet reduced this entity to its constituent parts that he still seems to be alive. “Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition?,” he asks. “Gods, too, decompose”. (p. l81) By separating God from the father, Freud began this process of disassemblage. However, he stopped before the job was done. The father, too, consists of multiple elements, and until we have also separated these elements from each other, Nietzsche’s “tremendous event” will continue to “wander.”

As Lacan suggests in Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis, what we generally call the “father” is actually a “function” – the “paternal function.” The paternal function amalgamates three different fathers: the actual father, the imaginary father, and the symbolic father. The first of these fathers is the flesh-and-blood person who is called upon to instantiate the other two. The second is the ideal paternal imago through whose prism we see the first when we imagine his love to be limitless. And the third is the abstract Law with which we confuse the actual father at those moments when we impute omnipotence to him.

Since the actual father is no more capable of meeting our demands than is the actual mother, this idealization would also lead to a radical deidealization if it were not for another crucial aspect of the paternal function: its insistence upon deferral. The latter uses the positive Oedipus complex to project far into the future the moment when the he must make good on his “promises.” The boy classically resolves his rivalry with his father and his desire for his mother by postponing the moment of satisfaction; the paternal legacy will indeed be his, but later. Because the girl classically enters the positive Oedipus complex only by signing away all claim to this legacy, she must accommodate herself to an even longer delay. The father will respond to the demands which she makes upon him later yet, and perhaps never. Through her enforced identification with lack, however, she absolves the father of all responsibility for her continuing dissatisfaction.

Christianity – which is the primary model both for Nietzsche’s and for Freud’s account of religion – adds a formidable new component to the paternal function: God. It posits a father whose love and power know no limits: the Divine Father. It also imputes to this father a son, who for the span of a brief lifetime assumed a finite form, and even became the repository of “sin.” Through this figure, Christianity bridges the distance between heaven and earth, permitting the actual father to represent the Divine Father, as well as the imaginary and symbolic fathers. This dramatically augments his power and authority, but even more importantly, it extends until the end of time the date at which his promissory note will come due. Christianity provides the actual father with a permanent safeguard against our disappointment and rage.

In Anna, Aki and God, Ahtila completes the decomposition begun by Freud by isolating the actual father from his imaginary and symbolic counterparts. She effects the first of these divisions by obliging us to see our own father in the quotidian form of the male speaker. She accomplishes the second in a number of different ways: by attributing to Aki himself the origin of the gaze by which he imagines himself to be seen; by foregrounding the male speaker’s loneliness; and by showing the stage upon which the latter appears to be in fact a desk – i.e., “make-believe.” Ahtila is able to separate the disparate pieces of the paternal function because she has already removed the “glue” which holds them together: the fantasy of an omnipotent but withholding mother.

The author of Anne, Aki and God marks the completion of this process of decomposition by moving the male speaker from the stage to the floor. The metaphor of descent is a risky one to deploy in this context. Because of its moral connotations, it could be read as a synonym for “fallenness” – for the failure of the paternal figure to assume the representational burden of fatherhood. This would situate him outside the coordinates of the actual father, and so leave the latter’s credentials unchallenged. We could also see the male speaker’s shift to the floor as a suggestion that he is not “up to the job,” and so as a reminder that the actual father is always “more or less inadequate” in relation to the imaginary and symbolic fathers. Although acknowledging the gap separating the actual father from the imaginary and symbolic fathers, we would then still leave intact the assumption that the latter constitute a legitimate standard for judging the former.

Ahtila goes to great pains to preempt both of these interpretations. As I have already indicated, she foregrounds the notion of an “audition” much more fully in the second half of her installation than in the first. One of the most important uses to which she puts it is to call into question the very idea that there is an actual father – to show that paternity, like maternity, exists only in the mode of a “try-out.” And fatherhood is not only provisional, but also open to constant revision and reinterpretation; there is no norm in relation to which a particular audition can be found “insufficient.”

Ahtila accesses the pure potentiality of paternity in the same way she accesses the pure potentiality of maternity: through finitude. And it is from the space below the stage that she does so. The first three times the male speaker appears, he remains in an elevated position. The fourth time, though, he first sits on the edge of the stage, and then abandons it altogether. The sequence in question is the one where Aki shifts from the topic of the execution to that of Anne’s tender gesture. As the paternal figure describes the psychic arena where summer and winter occur simultaneously, he moves about restlessly, as if he is not yet “at home.” However, when he says to Aki and us, “I miss you. I want to tell you something, and I will. I expose myself. I show you my face. I give you my life and my time,” it is from a relaxed and stationary position on the floor. He has finally found the place where he can be a new kind of father: not the actual father, but rather the human father.

As I have already noted, the first half of Anne, Aki and God ends with the story of Aki’s “cure.” The omniscient position from which the maternal figures narrates this story seems to mark the return of religious illusion. Before her words have stopped echoing in our ears, however, we begin to hear the irony which separates her from them. The installation as a whole concludes with the same narrative, but this time Ahtila detaches it altogether from the one who ostensibly speaks it. She has the paternal figure read it aloud from the script he holds in his hands, but to which he has until now barely referred. By transforming this text from a direct address to a quotation, without at the same time identifying its source, Ahtila deprives it not only of a speaker, but also of a recipient. She consequently makes it a tale from nowhere, that nobody tells, and nobody receives. This is what it means for God’s death to arrive.